In Focus: Women faculty continue to ask the University for support following the tenure clock extension’s end

May 27, 2021

Instead of digging through archives in Paris and Geneva, history Prof. Helen Tilley, a single mother, spent the spring of her sabbatical researching and writing on the bed while her then-11-year-old daughter completed virtual assignments next to her.

Tilley, a Northwestern faculty member since 2012, was on research leave in Cambridge, England. When COVID-19 caused worldwide shutdowns, Tilley and her daughter remained in their rented townhouse bedroom, which didn’t have room for a desk.

Her daughter would interrupt her several times each day about making lunch, walking the dog or completing her homework. Although Tilley said she wanted to help her daughter, the situation wasn’t conducive to getting her research work done.

“You want to be calm and positive about the interruptions, and you want to accept that that’s going to make it bearable for her to be out of school,” she said. “Every day is this balancing act of, ‘How much can I get written today?’”

Tilley said her daughter’s school wasn’t prepared for virtual learning. After three weeks of online work, Tilley said she began to find other ways to keep her daughter engaged and excited about learning, essentially creating a whole curriculum on top of her research.

She said everyone responsible for raising children is constantly trying to figure out how to balance their child’s needs while also advancing their own career.

“What do women do when they have a career goal, and then they have community issues that also rear their head where people’s well-being, your kids’ well-being matters or your students’ well-being matters?” Tilley said. “I go for the well-being first. It’s so important, especially for young people, to give security and to give support, because that’s what will make a difference in their lives.”

Over the past year, many faculty members, particularly women, have prioritized wellness over research and academic productivity. But when it comes to earning tenure, a near-lifelong appointment at a university, the quality and quantity of a candidate’s research, as well as their national reputation in their field, is crucial.

Time spent teaching, holding service positions within a department and working with students could all impact professors’ chances of being promoted. But positive Course and Teacher Evaluation Council surveys, or CTECs, don’t quite compare with an internationally-recognized name or research.

Across the country, fewer women are tenured compared to men. Women hold 49 percent of total faculty positions, but just 38 percent of tenured positions which means they typically earn less than those on the tenure track. At NU, a 2017 Provost’s Office report found that male full professors make just under five percent more than their female equivalents, and women spend more time at the associate professor level. Access to the data is restricted to University faculty members.

Even associate professors, who are tenured, have yet to reach the highest academic rank: full professor. The promotion comes with a salary increase, but women are 10 percent less likely to be promoted to full professor, according to the American Association of University Professors.

“Pre-pandemic, (it was) an unequal playing field for women anyway,” Tilley said. “It’s an unequal playing field for parents, the primary caregiver, which tends to be women, though it’s not always.”

“Thrashing in these waves”

The early stages of the pandemic disproportionately impacted women faculty across the country, who conducted less research, wrote fewer articles and had to respond to increased caregiving responsibilities in academia and at home.

There was already a gender gap in publishing before the pandemic — one study found that between 2014 and 2018, women accounted for just 38 percent of academic authors. And studies have confirmed gender disparity continued during the early months of the pandemic. There has been little research published about the recent months of the pandemic, but anecdotal evidence suggests this has continued into 2021.

Studies show men have submitted more articles for review during the pandemic. One study compared over 1,000 early papers on COVID-19 to more than 37,000 general papers from 2019 in the same journals, and found women’s authorship has dropped 16 percent overall.

One possible explanation for this disparity stems from changes in academic caregiving responsibilities. Faculty members said this has included supporting students as they navigate virtual learning and personal difficulties, such as the loss of family and friends. Professors also reported spending time assisting students in obtaining the technology they need and finding alternate ways to teach and connect with them.

Political science Prof. Mary McGrath faced increased at-home caregiving expectations in addition to her academic responsibilities. Instead of focusing on conducting research or publishing articles, she was taking care of her children, then ages 2

and 4, while her husband self-isolated due to health concerns from his kidney transplant.

“It was like me and my two boys thrashing in these waves,” she said. “I didn’t know what else was going on in the world, except from seeing what was happening in The New York Times.”

McGrath and her husband have handled child care themselves, each adjusting their schedule to take care of their sons when the other is working. Dressing and feeding her kids in the morning can take two hours, she said, so taking her next steps toward tenure was on her mind but not at the top of her to-do list.

“I was just trying to maintain my sanity and keep my two kids alive,” she said.

The track to tenure

Academic tenure was formally established in 1940 by the AAUP and the Association of American Colleges and Universities to provide lifelong employment to faculty members who show notable success in research and teaching.

A tenured professor can be dismissed only under extreme circumstances, such as sexual assault, fraud or the discontinuation of their program or department. While the exact figure at NU is not publicly available, as salary and funding is determined on a case-by-case basis, the average median salary of a tenured NU faculty member with a promotion to full professor was over $175,000 during the 2017-18 academic year, and over $136,000 for associate professors. NU’s data regarding gender disparities at the professor level is not publicly available.

Only 31 percent of faculty members on the tenure track at NU are women, according to the 2019 Diversity and Inclusion Report, which measured the University’s progress on its diversity and inclusion initiatives and the demographics of students, faculty and staff.

According to the AAUP, tenure was established to give select professors near-complete freedom of speech and research, as they cannot be fired for controversial research findings or political opinions.

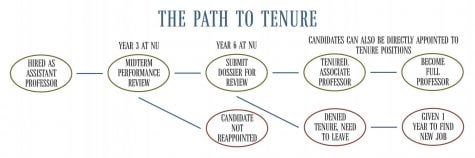

To be tenured, non-Feinberg School of Medicine faculty must submit a dossier to their department during their sixth year at NU including a curriculum vitae, copies of their research and at least five letters from tenured professors at other institutions. It also includes a personal statement with the candidate’s past teaching, research and service experience and future plans in these areas, according to the Policy on Tenure and Promotion Standards and Procedures.

To be more competitive, candidates for tenure often include over eight letters from professors at other institutions, and these can describe a candidate’s status compared to other professors in their field, the policy states.

The dossier then goes to a departmental committee and the school dean, followed by the Promotions and Tenure Committee. According to the policy, the candidate’s department writes a letter on the candidate and their work, and the committee provides a short summary of its discussion with an explanation for its vote.

After the addition of a letter from the school’s dean explaining the recommendations and rationale for each faculty member, the provost and president review the decisions before they are finalized. The dean informs the candidate of the decision, and the Board of Trustees approves the decisions over the summer.

While teaching and service are important for faculty who want to be tenured at a research university like NU, political science Prof. Karen Alter said the candidate’s quantity of research and the journals’ reputations are crucial.

NU’s Policy on Tenure and Promotion Standards and Procedures echoes this sentiment, stating that the quality, importance and creativity of scholarly work is most important when evaluating research, but the quantity of published work is a factor.

Provost Kathleen Hagerty did not respond to a request for interview, but she has been working with the OWF since the fall.

At an October 2020 forum between OWF members and senior administrators, Hagerty said she supported the OWF’s efforts. She added that she looked forward to working with OWF members to reduce preexisting inequities in academia, especially as they are exacerbated by the pandemic.

“Treading water”

In a September letter to senior administrators, the OWF called on the University to take 11 actions to increase gender equality and combat the pandemic’s impact. The letter included excerpts from 196 responses collected as part of an anonymous survey sent to all women faculty.

Responses outlined the professional and personal impacts of increased daily child care and household responsibilities.

“I have (only) had about 60 percent of my normal working hours because of caretaking needs,” one respondent wrote. “I’ve turned down an opportunity to write for a major popular newspaper because I don’t have child care. I’ve put my research on hold and feel as though I’m treading water.”

Another respondent said she’s provided a higher level of emotional support to her students since the start of the pandemic. This has included coaching and supporting six students as they prepared for an exam and four separate two-hour Zoom sessions with one student, for example.

Additionally, the respondent wrote that she supported Black students after the murder of George Floyd, and helped international students navigate the Trump administration’s policy changes to visa guidelines for those enrolled in virtual school.

Women faculty members of color also helped students process the police brutality and anti-Asian violence that have occurred over the past year. Although professors said they’re happy to support their students, the added volume of work takes an emotional toll on them.

The letter’s requests included a meeting with the deans and provost to discuss other suggestions, guaranteeing faculty the option to work remotely for the entire year, providing teaching relief and more options for child care and granting access to on-campus offices.

These pandemic-related uncertainties and increased responsibilities prompted NU to delay tenure decisions by a year. This decision was made as professors scrambled to move their classes online while simultaneously adjusting to life during the pandemic.

Sociology Prof. Christine Percheski was at home with her two young children, then ages 3 and 5, when NU shut down last March. She and her spouse kept a nearly constant watch over them while transitioning her graduate workshop to a virtual format.

As associate chair of her department, she had to support faculty and graduate students, coordinate teaching assistants and troubleshoot, all without a dedicated office space — and with her children running underfoot.

When stay-at-home orders ended, Percheski’s nanny was able to help with child care again. She said she and her husband are lucky they have assistance with child care, as many others can’t afford it.

“I was glad to be able to help my colleagues and our students, but it is draining and taxing work,” she said. “I love teaching, but I also love my research and I’ve just had very little time for research in the past few months.”

Percheski has taught more over the course of this academic year, which she said has taken up more energy. But she said she’s also been able to spend more time doing research as the year continues and vaccinations roll out.

Keith Bender, a professor at the University of Aberdeen, has been conducting research on how the pandemic has impacted women faculty members. Although all professors are dealing with challenges, regardless of gender, fewer women are tenured and more are teaching track faculty, so they end up with more teaching responsibilities, Bender said.

This causes women to bear the brunt of transitioning classes to a virtual format and other related work, which is even more difficult when compounded with increased child care, Bender said.

Department disparities

Not all women faculty members at NU are experiencing the pandemic the same way — individual schools and departments are taking their own approaches to equitable treatment.

The OWF has focused on taking action, writing reports and finding solutions. Separately, Feinberg’s Women Faculty Organization has supported women faculty members by holding a virtual meet and greet for them to connect. They’ve also hosted other online programming, such as speaker events and mentoring, said WFO co-chair and Feinberg Prof. Lisa Hirschhorn.

For some, the pandemic has created small opportunities to connect with family and students. Kellogg Prof. Angela Lee said she found herself with more time during the pandemic because she didn’t have to travel as much. She’s used the time to reach out to other faculty members and check in with students, especially international students, hosting daily, then weekly, coffee chats to build community.

Lee said another silver lining to the pandemic was the ability to teach from anywhere. Virtual classes gave Lee the ability to spend over a month in Canada with her daughter and grandchildren.

Medill Prof. Susan Mango Curtis said Medill has tried to be helpful, and has provided a lot of technology support. However, she said women faculty typically mentor students more and have taken on a “mothering” role with their students, in addition to doing the bulk of child care and housework.

Even though she doesn’t have any children at home right now, she’s made an effort to help those who do, especially after raising a child herself. When Medill asked Curtis to move her class time so another woman could help her children with online classes, she was happy to change time slots.

“I jumped to it,” she said. “I knew exactly what it felt like for someone struggling to deal with both worlds at the same time.”

The tenure clock is ticking

When NU announced it was pausing the tenure clock, the timeline tenure-eligible faculty follow as they apply to receive the appointment, McGrath said it seemed like a lifeline. The extension means that the file will be submitted a year later than planned, and no additional research, service or teaching will be expected. However, she said the solution feels like a temporary fix.

“It’s not going to be adequate to recoup what has been lost and what has changed and how this is affecting everyone’s capacity to do their jobs and take care of their families,” McGrath said.

Without the large chunks of time she used to have during her workday, she said she focuses during her children’s naps and after about 9 p.m. She said she tried to balance her family’s needs and her research but both were “suffering.” McGrath told The Daily the delay was essential but insufficient to make up for lost time.

The University’s tenure clock extension applies to tenure track-faculty who were still in their probationary period during the 2019-20 academic year. NU updated the policy this April, also giving tenure-eligible faculty who were hired during the 2020-21 academic year an automatic one-year extension.

Professors are typically granted tenure clock extensions for reasons like childbirth, adoptions or other extenuating circumstances, and they can only receive these on two occasions. However, the automatic extension does not count toward that maximum, nor does it prevent professors from receiving future tenure clock extensions.

Faculty can request a second pandemic-related extension that doesn’t count toward their limit of two if COVID-19 has upended their plans. They receive these by going through the typical process for tenure clock extensions.

Despite the extra year, preparing dossiers during the pandemic is still difficult. While an extension gives faculty more time to write their personal statement, obtain recommendations and update their CV, the extra year won’t always allow them to conduct research and complete larger projects. Many field and research projects needed to change entirely to be completed during the pandemic, Percheski said.

Percheski uses data at a federal restricted data center in Chicago, but it was closed for months, putting the project on hold. She said she couldn’t even access some of the data necessary for her research for five months.

As an already-tenured professor, these delays won’t determine Percheski’s job security, but they will for others. If an assistant professor isn’t granted tenure, they have a year to leave the University and find a job elsewhere.

Having to change a project or deal with personal issues arising from COVID-19 can complicate the path to tenure. With women being promoted and getting tenure at lower rates than men, these pandemic-related complications may further affect that disparity.

“It’s going to be hard to make up for this time,” Percheski said. “I don’t know if one year is going to be enough, especially for those with caretaking needs, or whose research was really impacted, and who have to redo research designs or wait for archives to reopen.”

Alter, who is on the editorial board of multiple journals, said she has watched submission rates soar, but men have been sending in more articles than women. This higher submission rate indicates men may publish more articles in top-ranked journals, giving them an advantage in the tenure process, she said. Because the quantity of published work is considered during the tenure review process, she said publishing research is crucial.

Due to the longer turnaround times caused by the pandemic, many faculty are submitting to less-prestigious academic journals because there’s a greater chance of acceptance, she said. However, she said women have done this more, especially pre-pandemic, which can hurt the quality of the file for promotion and tenure.

“That’s another way in which the male advantage is going to play out, (the) number of publications and placement of publications,” Alter said. “It’ll play out starting next year, it’ll have a long tail.”

Moving forward

The pandemic has altered academia and affected faculty even beyond transitioning classes to Zoom, taking care of their family members and contracting COVID-19. Community members have been pushing for tangible action to promote gender equality on campus.

The OWF’s September call to action requested the implementation of ombudspeople at various institutional levels, providing support to faculty.

An ombudsperson is a “neutral, independent, impartial and confidential” third-party that works to solve academic and work-related problems and conflicts. In addition to conflict resolution, an ombudsperson directs faculty to University resources or policies.

After a nationwide search, NU named Sarah Klaper the first University ombudsperson two weeks ago. She will start on Aug. 1 after serving in the same position at Northern Illinois University for nine years. Klaper will report directly to the provost and is responsible for creating an Office of the Ombudsperson.

While this is a single position, an ombudsperson can advance the OWF’s goal for University personnel tasked with reaching out to faculty and advocating for those who need accommodations and support.

The OWF also requested NU appoint a new associate provost for faculty. Hagerty held the role before becoming interim provost in April 2020, then provost on Sept. 1, 2020. After a 10-month vacancy, Sumit Dhar, formerly the chair of the Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders and the associate dean for research in the School of Communication, stepped into the position on Feb. 1.

All of the OWF’s 11 requests have been acknowledged, and at least nine have been addressed in various ways. Some schools and departments have made advances quietly, such as reopening offices, reducing non-essential events and providing various avenues for teaching relief.

Alter said the OWF is still working toward equality while the pandemic’s lasting impacts remain to be seen.

“Because (of) this year, you really can’t use the standard practices — to use the standard practices will exacerbate inequities, which is what everybody’s been worried about,” she said. “So now we have a historic moment to actually address past inequities to say we can’t use the old metrics.”

Moving forward, faculty will keep fighting for equitable pay and inclusive promotion and hiring practices so women, gender minorities and faculty of color will be considered and their various experiences and hurdles will be taken into consideration when decisions are made.

On May 14, NU announced the Diverse Slates Candidate Policy, which defines new mandatory hiring practices as part of June 2020 commitments to social justice. It will require diverse representation on hiring committees and partnerships with affinity groups.

In addition to equity in hiring, NU has identified the need to rectify a gender gap in faculty salaries. University President Morton Schapiro told The Daily on May 21 that the disparity can be addressed by the current budget surplus.

“It’s been very difficult because we’ve been in a situation where we’ve kept salaries flat,” Schapiro said. “I think we’re now in a position, now that the budget’s back in surplus, to really address any residual imbalances that were discovered… Now that we’ve reinstituted increases for the faculty, it’s a chance to address it.”

Right now, many women faculty are focusing their advocacy efforts around preventing sexual assault and racism, especially after Mike Polisky was initially chosen as the University’s next athletic director, only to resign 10 days later.

Polisky came under fire because of his handling of complaints of sexual harassment and racism on NU’s cheer team. He was also named a defendant in a lawsuit relating to his responses to sexual harassment complaints. As a result, the OWF released a statement on May 13 in response to Polisky’s promotion.

[Read The Daily’s February investigation into allegations of racism on the cheer team.]

“The University’s response to recent events and allegations regarding the cheer team is deeply problematic, illustrating the power dynamics that perpetuate sexist and racist harassment and contribute to a toxic climate for women faculty, staff, and students and members of minoritized groups,” the statement read.

These minority communities aren’t just limited to cisgender women faculty and faculty members of color. Political science Prof. SB Bouchat said the University focuses too heavily on traditional conceptions of gender, and should acknowledge the different needs of gender non-conforming and transgender faculty.

“There is a really acute and serious concern for people who have child care responsibilities, but I do think that leaves a lot of other aspects of gender out of the conversation,” Bouchat said.

While administrators and advocates push for short- and long-term changes to advance gender equality at NU, it’s still hard for women to keep on top of teaching, research and personal responsibilities. Additionally, professors continue to support their students, make virtual learning gratifying and manage their personal lives.

However, Tilley said acknowledging the gaps and working toward closing them has helped people feel like someone has their back, even though systemic change is still necessary.

“Quick thinking and flexibility can make a big difference in helping people feel like, even if there are not big institutional changes, there’s a leadership that sees that there’s a problem and recognizes a problem,” Tilley said. “That actually can make a big difference to morale.”

Email: haleyfuller2022@u.northwestern.edu

Twitter: @haley_fuller_

Related Stories:

— Organization of Women Faculty talks equity amid COVID-19 with Provost, deans